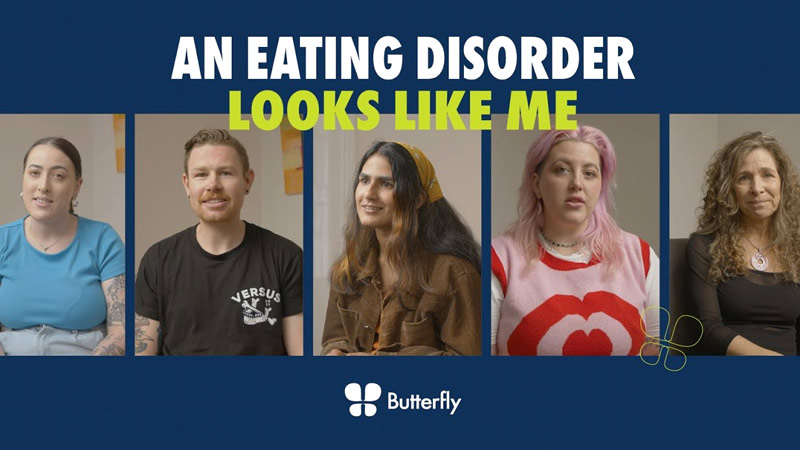

Many of us have a general view of what an eating disorder “looks” like. Typically, this is an emaciated, white, young female. However, the majority of individuals who meet diagnostic criteria for an eating disorder do not fit this image.

Too often when networking with general practitioners (GPs) and allied health professionals, we hear “I don’t have any eating disorder patients”. Recently, at a GP networking lunch, a senior GP admit that for most of his career, he only considered the possibility of an eating disorder if it was “blatantly obvious” (i.e., fit the stereotypical image of what many believe an eating disorder looks like).

This is a view that many health professionals share, as well as the general public. However, eating disorders prevalence data suggests that a GP sees (either knowingly or unknowingly) at least one patient with an active eating disorder each day. In fact, according to the Butterfly Foundation, 1.1 million Australians were actively living with an eating disorder in 2023, a 21% increase since 2012. This is equivalent to 1 in 23 people (Butterly Foundation, 2024). Eating disorders have the highest mortality and morbidity rates of all other psychiatric illnesses, with one life lost every 52 minutes as a direct result of an eating disorder.

Despite the significant prevalence, it is estimated that many people in Australia with an eating disorder will not seek professional help, suggesting that the actual number of affected individuals may be higher than reported. While there are various reasons as to why this may occur, one significant factor is that individuals who do not fit the stereotypical mould of what an eating disorder “ought to” look like have their symptoms overlooked by medical and mental health professionals.

Furthermore, when symptoms are acknowledged, they are frequently perceived to be less severe and life threatening, meaning that these individuals do not receive appropriate care and monitoring for their serious illness.

Just because an individual may not be in a smaller body does not mean that their eating disorder is less severe.

Recognising Potential Signs of an Eating Disorder

The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidelines outline that the best thing any health practitioner can do for the treatment of an eating disorder is considering that an eating disorder may be present in the first place.

There are many factors that place an individual at an increased risk of developing an eating disorder (i.e., low self-esteem, perfectionism, trauma history, experiences of weight-based bullying, body dissatisfaction, etc.), but research shows that dieting and/or weight loss (whether this be intentional or unintentional) are the strongest predictors of the onset of an eating disorder.

For this reason, we strongly encourage that the following screening questions be asked of all patients to gain information as to whether an eating disorder may be present:

- Have there been any changes to your diet, eating patterns, or behaviours?

- Have there been any changes to the amounts/types of physical activity that you engage in?

- Have there been any changes to your body weight?

- For adults: What is your highest (non-pregnancy) adult weight vs. your current weight?

- For children: How does your child’s current weight compare to their weight trajectory over time?

If a patient reports of endorses concerns with food, eating, and/or their body weight/shape, they may have an active eating disorder that requires further investigation and assessment.

Eating disorders Do Not Have a “Look”

While the mortality rates are highest amongst individuals with Anorexia Nervosa, only 3.5% of individuals known to the healthcare system had a diagnosis of Anorexia Nervosa in 2023 (Butterly Foundation, 2024). Of all eating disorders, Unspecified Feeding or Eating Disorder (UFED, 34%), Other Specified Feeding and Eating Disorder (OSFED, 27%) and Binge Eating Disorder (BED, 21%) were the most common, making up 82% of all individuals with a diagnosed eating disorder.

These individuals are unlikely to fit the stereotypical mould of what an eating disorder may look like, yet they make up a significant portion eating disorder cases. This highlights the importance of recognising eating disorders across all body types, genders, ethnicities, and backgrounds, and more likely than not, an eating disorder will look very different to what we may expect.

For more information on screening for, assessing, managing, or supporting a loved one with an eating disorder, please feel free to contact our friendly Client Care Coordinators on 07 3161 0845. Full recovery from an eating disorder is possible with specialised treatment, and identification and accurate diagnosis play a critical role in ensuring that the best health outcomes may be achieved.

References

Butterfly Foundation. (2024). Paying the price, second edition. The economic and social impact of eating disorders in Australia. https://butterfly.org.au/who-we-are/research-policy-publications/payingtheprice2024/.