Regular exercise participation is prescribed for many people with physical and mental health conditions. Suggested benefits of exercise are multiplying daily as science discovers more about the human body. How do we know, however, when exercise no longer supports (and rather, degrades) our patients’ health?

‘Harmful exercise’ describes exercise behaviours that degrade, rather than enhance, an individual’s physical, mental, social, emotional, spiritual, and/or environmental health.

Calogero and Pedrotty (2004) identified three key points to consider when assessing whether exercise is helping or harming your patient. In order for exercise to be regarded as ‘healthy’, they suggested that it must:

- Rejuvenate the body, not exhaust or deplete it;

- Increase mind-body connection, not allow or induce disconnection; and

- Alleviate mental and physical stress, not produce more stress.

How to raise concerns about harmful exercise?

Your patient presents with a QTc interval of >450ms as well as electrolyte abnormalities. Upon raising your concerns with your patient, they also inform you that they restrict their dietary intake, purge (i.e., vomit and/or use laxatives) regularly after meals, are exercising to lose weight, and experience excessive guilt if/when they miss an exercise session.

Your concern escalates as you consider the risk of an adverse health event (i.e., sudden cardiac death) occurring should your patient continuing exercising whilst engaging in these detrimental health behaviours. You recommend exercise abstinence until these behaviours cease.

Your patient’s distressed response to this recommendation suggests that exercise may be their only mechanism for managing challenging emotions. You correctly identify one of three negative outcomes are likely to occur:

- They disregard your advice and continue exercising dangerously

- They resort to other harmful coping strategies (i.e., self-harm, drug/alcohol misuse)

- Their mental health further deteriorates

What do you do now?

CFIH Exercise Physiologist, Alanah, is currently developing exercise and eating disorder guidelines, SEES: Safe Exercise at Every Stage, aimed to support practitioners in safe exercise prescription.

Until the guidelines are published, Alanah has the following suggestions for identifying and managing harmful exercise engagement in your patients:

1. Ask questions. Try to gather as much information as you can about your patients’ exercise behaviour. As well as determining the extent of physical and psychological risk involved, you’re encouraging them to consider the impact of their exercise beyond weight management.

- Do you feel guilty if you miss a workout?

- Do you still exercise when you are sick or hurt?

- Do you miss going out with friends or spending time with family, just to ensure you can complete your workout?

- Do you feel anxious or agitated if you miss a workout?

- Do you calculate how much to exercise based on how much you eat?

- Do you have trouble sitting still because you’re not burning calories?

- If you’re unable to exercise, do you feel compelled to cut back what you eat that day?

2. Find common ground. As health professionals, we know the optimal health behaviours that would benefit our patients. However, we must also acknowledge that change is a collaborative process and only occurs when we meet people where they are at. Rather than assuming the expert stance, try to engage your patient in a collaborative discussion about their exercise behaviour. Ask for their opinion about the appropriateness and sustainability of their current exercise regime. Query what their response would be to a friend who told them that they were exercising in the way that they report exercising. Enquire about the amount of exercise they feel would be healthy – for themselves, and for others. Ask them why they exercise as well as the reasons they think that other people exercise.

3. Provide education. Highlight the current risks associated with their current exercise behaviour and assist them in seeing that (contrary to their intended outcome) they are moving away from, not towards health.

4. Create a contract. Collaboratively develop an exercise plan that you (as the medical/health practitioner) feel is safe and the patient feels they can realistically adhere to. When devising a plan, be as specific as possible. Include the exercise frequency, intensity, time and type, as well as nutrition required pre, during and post-exercise. Both agree to and sign the plan, signalling your joint commitment to it.

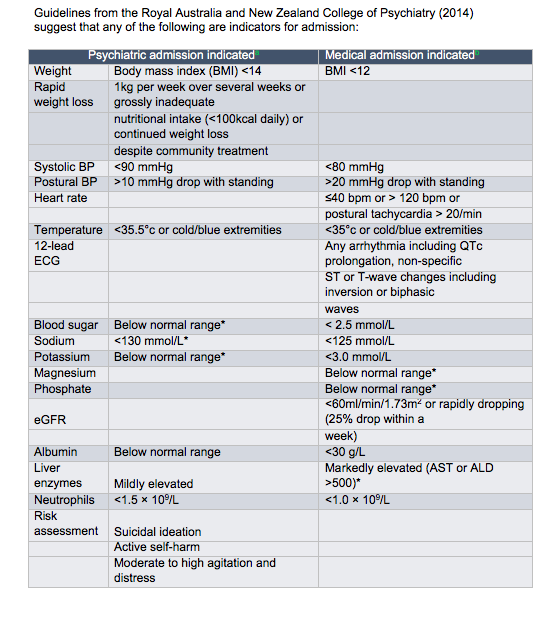

5. Regularly monitor. Advise the patient that to continue exercising, they will require weekly reviews. As per the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of eating disorders, you might want to consider the following investigations:

- Lying to standing heart rate and blood pressure

- ECG

- Body temperature

- Serum biochemistry

In summary

Safe exercise engagement can improve the well-being of most patients, however, it must be managed appropriately to avoid negative health consequences (especially for people with eating disorders). The Safe Exercise at Every Stage (SEES) guidelines for eating disorders are scheduled for publication next year. In the meantime, please contact Alanah with any questions and/or for her collaborative input in your patients’ treatment.